This selection of videos from the MUSEUM MMK FÜR MODERNE KUNST collection is framed around the movements of choreography, repetition, circulation and the emotional expansions in storytelling.

Draw a circle, and follow the same movement again; the two circles would never appear the same.

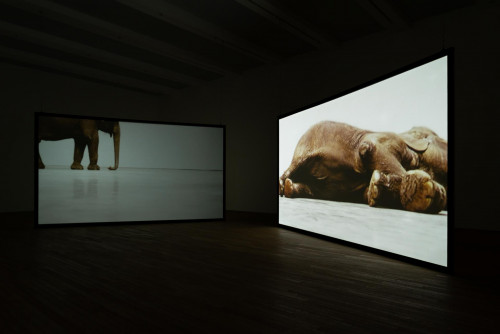

The repetitive acts of Minnie in Play Dead, Real Time (by Douglas Gordon, 2003) has the four-year-old circus elephant obeying simple instructions from her trainer: “Now lay down and play dead.” Her ponderous body slumps on the floor, soundless, and struggles to rise from her knees, her muscle movements captured in high-speed circling shots, creating a strangely coherent rhythm of the slowness of falling with a speedy camera performance. In the next room, the dancers Ander Zabala and Amancio Gonzales enact a daily rehearsal of Stellentstellen (by William Forsythe, 2013): “hand to toe, and toe to hand”, their limbs are entangled, while their bodies are combined in a knotted constellation, a rotating movement that subtracts physical elements and identities. Nearby are early video works by Rosemarie Trockel: Ei Dorado (1992), á la Motte (1993), Parade (1993), Egg trying to get warm (1994). Away from the living bodies, the artist brings her wit in animating quotidian objects of domestic conditions: stitched threads and eggs are choregraphed to dance, unravelling the freedom of being something else. The unassuming femininity is ubiquitous in Trockel’s oeuvre, as seen in her work Hair (1997)—installed on the screen at the entrance of the building, the video loops, in slow motion, an image of a woman on a motorbike, her long blonde hair fluttering in the air (a clichéd image of women in commercials). Yet the biker in focus is in fact one in a group of women bikers (all with blonde hair), riding towards an endless road in the summer breeze—subverting male virility in motorcycle imagery.

From bodily acts to the circulation of emotions, Soft Film (by Sara Cwynar, 2016) narrates the artist’s collection of eBay purchases, consisting of dated jewellery boxes, mostly mounted with such typical soft fabrics as velvet or silk. The film is composed in the tradition of a film essay, with the artist herself on camera, archiving and arranging objects and found images, speculating on their lives through their circulation on the internet, as well as their ownerships and economies. “Soft misogyny”, as the artist pronounces it: how such soft and exquisite objects are designed to satisfy women customers, and yet are only subordinate to the content. While her script is prepared to be read out by a male voice, the artist constantly corrects the reading as a live editing.

John Baldessari’s Six Colorful Tales: From the Emotional Spectrum (Women) (1977) is a series of interviews where the artist asks six young women the same question: share a crucial incident in your past. The speakers are set on a coloured backdrop in the manner of “talking heads” where the artist tunes the colour temperature to reflect the emotional turns in their stories, ranging from joy and humour to trauma and pain, with the element of violence recurring. A similar transformation of emotional intensity is staged in Bruce Nauman’s Good Boy Bad Boy (1985), where two professional actors recite one hundred phrases all connected with the “good boy”. As the readings repeat, the tone of the voices changes from neutral to anger as though on a gradual curve; as the two videos run to the end, the two speeches are out of rhythm, having transformed from a harmonious duet to a heated, clashing quarrel. On the other side of the space stands Soziale Plastik (Social Sculpture, by Lutz Mommartz, 1969). The filmmaker asked the pivotal artist Joseph Beuys to be on his camera and not blink—a simple gesture of exposing oneself to an anonymous audience. Beuys becomes the sculpture in moving image, in his attempts of staying still. Echoing Minnie’s falls, these wordless, poignant motions make up the form of a steady circle.